by Julius Lacano

“Les sanglots longs des violons de l’automne” (“The long sobs of autumn violins”),

“Blessent mon coeur d’une langueur monotone” (“wound my heart with a monotonous languor”)

From Chanson d’automne by Paul Verlaine, 1866

These words, spoken to the French Resistance over BBC Londres, signaled that the liberation of Europe was at hand. While 60,000 resistance members got to work destroying supply and communication lines, hundreds of thousands of Allied soldiers, sailors, and airmen waited for what Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel described as “the Longest Day.”

As the 80th anniversary of Operation OVERLORD draws closer, the Museum looks to commemorate the lives of all those who fought and “gave their last full measure of devotion” to liberate Western Europe from Nazi tyranny. Through the “blood, toil, tears and sweat” of over 2 million people from 12 countries, the Allies were able to launch the largest joint air and sea invasion in history. Victory on June 6, 1944, was never guaranteed; both the Allies and the Germans had spent years preparing for this day. Much of it because of a disastrous operation that took place on August 19, 1942, known as Operation JUBILEE or the Dieppe Raid.

Since entering the war on September 1, 1939, the British suffered defeat after defeat. They were forced off the continent in 1940 after the surrender of their ally, France, and the following years did not prove any better Even though the United States entered the war after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Britain had been pushed out of modern-day Malaysia by the Imperial Japanese Army, underwent a humiliating surrender in Singapore, and was fighting both the Germans and Italians across the sands of North Africa. Simply put, they needed a break.

Vice Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten was busy planning commando raids across Northern France as a Combined Operations Headquarters (COHQ) member, an agency founded to organize, plan, and undertake special operations during the war. These daring attacks on enemy territory provided a sense of progress, demonstrated that the Allies were honing their skills, and showed the war-weary public that they could defeat the Germans on their home turf, raising morale.

The most notable raids were the Brunevaland and St. Nazaire Raids in February and March 1942. The first was a British Airborne operation that inserted paratroopers and technicians near a German radar installation to capture equipment for British researchers. British technicians disassembled the radar after neutralizing the troops guarding it and capturing one of the operators. The British forces, the captured German, and pieces of radar equipment were ferried back across the Channel to England.

The second could be called the most incredible special forces action ever. This raid targeted the port and dry docks at St. Nazaire, the only port on the Atlantic coast large enough to accommodate the German battleship Tirpitz. At 1:34 am, the destroyer HMS Campbeltown, disguised as a German warship escorted by 17-armed Royal Navy boats, crashed through the gates of its target, the Normandie dry dock, all the while under attack from dozens of German guns. Commandos then rushed off the ship to destroy necessary dry dock equipment, such as pumps and the machinery to open the now heavily damaged gates.

As the Commandos watched each of their escorts get sunk one by one, they realized that only three options remained: to find a way back, to fight on, or to be killed. The three surviving boats loaded as many Commandos as possible and escaped, fighting until they reached the open sea. The rest of the Commandos fought till they ran out of ammunition and surrendered. Of the 612 Royal Navy and British Army personnel that took part, 228 escaped, 169 were killed, and 215 were captured.

But after the fighting stopped, the Germans were startled by an even larger surprise. At noon, time delay fuses ignited four and a half tons of high explosives hidden in the ship’s hull and encased in concrete. The explosion shattered windows, killed over 350 Germans, and destroyed the dry dock, rendering the dry dock inoperable until 1948.

Though COHQ had shown its skill in numerous successful engagements, two forces soon pressured Mountbatten and the rest of his command. The first was Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin. In 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union with 3.8 million troops despite a non-aggression pact between the two countries and a secret agreement to divide Europe between them. Though the Soviets pushed the Germans back from the gates of Moscow, Germany and her allies Italy, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, and Croatia pressed forward toward the Russian city of Stalingrad. As Stalin looked at his situation, with military and civilian losses pushing further into the millions, his army depleted, tired, and stretched thin across several thousand-mile fronts, he begged the US and Britain to invade western Europe as soon as possible.

This brings us to the second force: Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Churchill, for his part, pressured Mountbatten for more extensive and significant raids that allowed the Allies to develop training, tactics, and equipment to aid in their invasion of France. Churchill also wanted to show Stalin and the British public that he supported his Soviet Allies, provide an opportunity for Canadian troops to gain combat experience, and conduct an experiment in amphibious warfare.

This “experiment” was founded on the reality that any invasion of mainland Europe would require capturing and holding a French port long enough to get troops and equipment into battle. Beyond that, the Allies lacked real experience in amphibious operations especially those on defended beaches, and they did not know how armor could be used to support troops moving inland. They also had little knowledge of German shore fortifications. Conceived as a large, full-scale amphibious landing with paratroopers, heavy bombers, close air support, and naval bombardment, this raid, under the code name RUTTER, would provide the experience to solve all these problems. However, attacks by German bombers and foul weather canceled the operation. The Allies looked for an alternative and conceived a new one: JUBILEE.

Stay tuned later this month for the second installment of From Disaster to Victory to learn more about Operation Jubilee aka the Dieppe Raid.

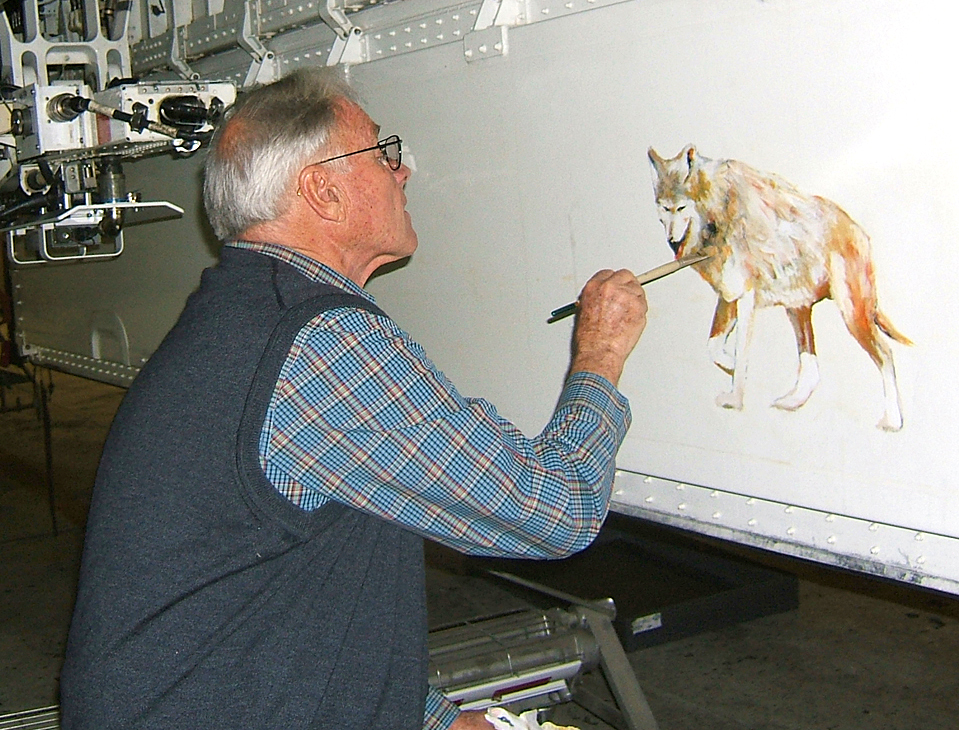

To continue learning about the lead up to D-Day, visit Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum on June 8 for Remembering D-Day: Commemorating the 80th Anniversary. Admission includes a screening of the D-Day film, followed by an engaging panel led by our Education Director and featuring Boeing Senior Historian, WWII Veterans, a C-47 expert, and more. Drop by the Aviator Café for a discounted bite to eat before soaring to new heights with a WWII-focused tour centralized around our C-47 Skytrain that flew in the Battle of Normandy.